We didn’t fish much in Kentucky. We ate a lot, drove a lot, and we saw a lot of whiskey being made. We bought a lot of whiskey because a gallon of whiskey was cheaper than a gallon of gas, so we filled up the car with whiskey.

Not really. Almost, but not really.

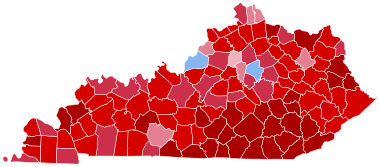

It was cold in Kentucky, and getting colder, and it was wet. This matters because I wanted to fish for smallmouth bass. Smallmouth are native to states west of the Appalachians and east of the Great Plains, and north from Arkansas into Canada. That includes Kentucky. Trout are kind of a mystery to me, bass less so, and I wanted to catch a home-grown Kentucky fish. Native wild fish–as opposed to an introduced wild fish or a stocked fish–are my beau ideal, and trout aren’t native to Kentucky.

In early March there are stocked trout all over Kentucky. In most streams they’ll die out in the heat of the summer. In the Cumberland River below the Wolf Creek Dam trout are stocked year-round. Absent drought, the dam-released water is cold enough for trout, but it’s not really a wading river, and we didn’t have a boat and I hadn’t hired a guide.

Like the other black bass, smallmouth hunker down when it’s cold, and for anything fishing is almost impossible when streams are churned and fast with runoff. When we got to Kentucky, there was water standing in the fields, and the streams we saw from the road were dark grey and ugly. The lady at the gift shop at the Trappist monastery told us there had been five inches of rain in two days. Ladies at Trappist monastery gift shops surely don’t mislead, at least about rain.

I did make a weak effort for smallmouth. We had planned on two days fishing, Tuesday and (if we didn’t catch a fish on Tuesday) Thursday. I’d found two creeks that promised wading for smallmouth, Otter Creek near Louisville and Elkhorn Creek near Lexington. On Tuesday we drove the 30-odd miles to Otter Creek, but I didn’t get to see the creek. The Recreation Area is always closed on Mondays and Tuesdays.

I had a back-up plan, but it involved trout, and a particularly peculiar trout stream.

If you think about Kentucky, it’s shaped a bit like a frying pan lying on its side, with the panhandle on your left. Louisville, where we were staying, is at the very top of the pan on the north. The south along the Tennessee border is buried in sand so it’s flat, and the weird stream, Hatchery Creek, is almost due south from Louisville on the other side of the state. What did we care? There was plenty of whiskey for the gas tank.

Before I tell you about the weird stream, I have to tell you about my new fly rod.

I have all the fly rods that I will ever need, and plenty of extras just in case, but a few weeks ago my friend Mark Marmon texted and asked if I wanted a bamboo fly rod. Mark’s texts sometimes get me into trouble. I have a new used Schaeffer jazz guitar because of a text from Mark, and next year I’m going to Cuba to fish because of a text from Mark. In addition to being an Episcopal priest and fly fishing guide, Mark is a great scavenger. He regularly makes the rounds of the pawn shops and estate sales, he studies Ebay, and people–especially fly fishing people–give stuff to Mark.

Mark said that he had too many bamboo fly rods, and asked if I wanted one. If you don’t fly fish, this takes explanation. From roughly 1870 through 1960, the best fly rods were made by splitting bamboo into six pieces, shaving the pieces into tapered wedges, then gluing together the wedges. There were legendary bamboo fly rod makers like Leonard and Garrison. There were fine company makers like Orvis and Winston and Hardy–Hemingway famously fished with English Hardy rods. There were very good rods, Heddons and Shakespeares, South Bends and Pflueggers, made for sale to the common man at his local hardware store.

There was also junk, but there’s always junk.

In bamboo’s heyday, anglers used silk fly lines and sheep gut leaders. I don’t think they used bone hooks, but maybe. Unlike silk fly lines and sheep gut leaders, bamboo rods are still popular, though not common. They’re organically beautiful in a way that modern graphite rods can’t be. They feel different, slow and soft and heavy, and some people, especially trout anglers, really like how they fish. And they’re collectible. An antique Garrison in great condition might go for $10,000. An antique Heddon in good condition might sell for several hundred dollars. A new bamboo rod–and there are very good rods being made–might cost several thousand dollars.

Mark wasn’t offering a several thousand dollar rod. He was offering a fine hardware-store quality rod, a Heddon Thorobred. I grabbed it, because, after all, one ought to fish a Thorobred in Kentucky. I did buy Mark lunch at Blood Brothers Barbecue. It was a very good lunch, but not as good as the fly rod.

According to the internet, Heddon stopped making bamboo rods in 1956, the year I was born. By the markings on the rod, it was probably made after 1933 but before 1939. I’m no expert, and that’s a pretty wild guess based on an hour or so of internet browsing, but the gift rod is possibly a couple of decades older than me, and is at least as old as me.

It’s really old.

That’s the rod I took with me to Kentucky, a #14 Heddon 9′ split bamboo rod for an HCH line, whatever that is. It’s a lovely thing.

Now I have to tell you about that weird Kentucky stream.

Hatchery Creek where we fished in Kentucky is one mile long, about 20-feet wide, and completely man-made. It’s a stream that before it opened in 2016 never existed in nature. I knew it wouldn’t be blown out because it’s not fed by rain; it’s fed by releases from the Wolf Creek Dam at a constant 25-35 cubic feet per second. Some combination of engineers and fish biologists planned every foot of Hatchery Creek. They planned the bends in the stream, the twisting channels, and the placement and the depth of the big rocks. They hauled in the fallen timber. Not only that, the creek is directly below the Wolf Creek National Hatchery, so there’s a ready supply of stocked trout.

Did I say I wanted wild, native fish? The first 100 feet or so of the stream is a put and take fishery. Anybody can reach it, and short of batteries or dynamite, anybody can fish with whatever they want. Anglers can keep up to five fish. There were people there completing their grocery list, and I suspect they had their five fish after 20 minutes.

Then there’s a fish dam, and below the first 100 feet the fishing is catch and release, artificial lure only. The fish presumably come up from the Cumberland, though maybe there’s some stocking going on to. Here’s the really weird part: if you didn’t know the area below the put-and-take was man-made, you wouldn’t be able to tell. I knew in my head that somebody had placed that streamside log to jut into the stream just so, but it’s still a jutting log, and it’s still a stream. It looks completely natural. Still. It just ain’t natural.

At least that day I was the only person who walked downstream from the put and take fishery. Well, Kris walked down, but she didn’t stay long. She stayed at the put-and-take and talked to people, and watched hatchery trout perform synchronized swimming routines around her fly.

I did do all the things necessary to make my time on the stream as authentic as possible. I lost my flies on a rock in the river and had to re-rig. I got my flies hung in trees, and then got them hung in the creekside brush when I pulled them out of the trees. I had to sit down creekside and work through a mare’s nest of hooks and monofilament. I lost my landing net, then I found my landing net hung in creekside brush where I’d half-climbed to release my snagged line.

It was a complete fishing experience, and after about an hour I caught an 8″ rainbow and called it a day. That’s when I discovered I’d lost my landing net. At least I caught my stocked rainbow on a non-existent Kentucky stream using an 80-year old rod. The rod was pretty cool.