We go to Maine on Friday, via United Airlines to Bangor and then north from Bangor by car, past Mount Katahdin and Baxter State Park, further into the north woods to Piscataquis County, about as far north as counties in the continental States dare go. I’ve never been to Maine, and we’ll be so far north that to our left, to our right, and straight ahead all the land will belong to Canada. It’ll be just like the Charge of the Light Brigade, though hopefully without the cannon.

Did you know that there’s more Allen’s Coffee Brandy sold in Maine than anyplace else? Did you know that there’s something called Allen’s Coffee Brandy? Until sometime in the early 2000s it was the most popular liquor sold in Maine, though now various vodkas are higher on the list. It’s still well up there. There’s also a popular regional soft drink called Moxie, and in Maine the mix of Moxie and Allen’s Coffee Brandy is called a “Burnt Trailer.” The mix of Allen’s Coffee Brandy and Diet Moxie is called a “Welfare Mom.” Even in the interest of science, I doubt that I’ll try either one.

Moxie, by the way, was originally sold as a tonic brewed to prevent softening of the brain, nervousness, and insomnia. I might could use some of that. Moxie and vodka, by the way, is a Moxie mule.

Maine has a population of 1,372,000, 92% Anglo, with a total area of 35,385 square miles. That puts it 38th on the list of states by population density, ahead of Oregon, Utah, and Kansas. Roughly 80% of Maine is forested, and most of it’s population is in the remaining 20%. It’s the largest New England state. With a few exceptions, Mainers cluster reasonably close to its coast, but even along the coast there aren’t large urban centers. Maine’s largest city, Portland, has a population of 68,424. Lewiston, the second city, has 38,493. In the north and west of the state there’s forest, and some mountains, too. The north end of the Appalachian Trail is Mount Katahdin, 5,269 feet. Then there’s some more forest.

About half of the population lives in the southeast corner around Portland. All of the reported vampire population is in Jerusalem’s Lot, and hopefully they’ll stay there.

William Bradford, The Schooner Jane of Bath, Maine, 1857, oil on canvas, Art Institute of Chicago.

Reading Maine history is peculiar. Until the Civil War, Maine seems to have been the hottest thing going. They built ships in Maine. Maine’s captains sailed the world. Maine produced timber, and there was land to be had. That’s not to say that Maine didn’t have its troubles: the English were prone to try to move the border, and Mainers had to rid themselves of Massachusetts. There were always French folk trying to migrate south from Canada. Into the 20th Century though if you bought a shoe it was like as not made in Maine. If you bought a sailing ship it was like as not made in Maine.

Then winter came, and it wasn’t. L.L. Bean boots and Hinckley Yachts are still made in Maine, and there must still be a Bath Iron Works, but I think Maine’s most significant exports now are Steven King novels and potatoes. Even Allen’s Coffee Brandy and Moxie are made in Massachusetts.

Jacobson, Antonio N., S.S. State of Maine, ca. 1892, oil on canvas, Maine Historical Society. The S.S. State of Maine was built in Bath, Maine.

Before the Civil War Henry David Thoreau wrote three travel essays about Maine, two of which were published in periodicals during his life and collected after his death as The Maine Woods. His trips weren’t far from where we’re going. On one trip he climbed Mount Katahdin. On another a Native American guide took him and a companion by canoe to Moosehead Lake. Some of the essays are pure travelogue, but they’re well written and appealing, with enough wilderness spark to provide drama. Some of the writing is better than mere travelogue. From time to time in The Maine Woods you’ll find some of Thoreau’s loveliest observations about nature, and nobody ever did mysticism and nature better than Thoreau.

Is it the lumberman, then, who is the friend and lover of the pine, stands nearest to it, and understands its nature best? Is the tanner who has barked it, or he who has boxed it for turpentine, whom posterity will fable was changed into a pine at last? No! No! It is the poet . . . . ((Thoreau, Henry David, “Chesuncook”, The Maine Woods at 112, Yale University Press 2009, New Haven, Ct.))

You’ll also find his god-awful attempts to reproduce the dialogue of his Native American guide. Tonto’s script writers produced less stilted vernacular. “Kademy . . . good thing–I suppose they usum Fifth Reader there . . . You been college?”((Thoreau, Henry David, “The Allegash and the East Branch”, The Maine Woods at 183, Yale University Press 2009, New Haven, Ct. Interestingly, “that looks like Ned and the First Reader” was my father’s standard description of messy work, as in “your casting looks like Ned and the First Reader.” I never knew there was more than one Reader until I read Thoreau. I still don’t know who Ned was.)) After reading Thoreau’s dialogues, you realize why his best work is about living alone at Walden Pond.

Paul Bunyan statue, Bangor, Maine. Paul Bunyan was also resident in Michigan, Minnesota, and Nova Scotia.

In The Maine Woods, Thoreau mentions the red shirts of the lumbermen several times. I thought certain that when we got the gear list for Libby Camp it would require us to bring red flannel shirts, but there was nary a one listed. These days anglers are more prone to camouflage than red, on the theory that fish will more easily spot threats who wear bright colors. Whatever the styles preferred by 19th century Maine lumbermen or 21st century fly fishers, it’s hard now to find a red flannel shirt, even with the help of the internet. The closest I could come was an L.L. Bean chamois shirt, probably made in China, and somehow the notion of buying a heavy shirt during the current Houston heat wave was just more than I could stomach. I’ll wear no red in Maine, and I apologize to Henry David and Paul Bunyan.

We could go to Maine to fish the seacoast. It’s a drowned seacoast, a seacoast that because of rising oceans after glacial retreat left a rugged and interesting shore. This time of year there should be not only striped bass but migrations of bluefish and false albacore. I do get seasick though.

Cornelia “Fly Rod” Cosby, the first registered Maine guide.

There was also a time when you could go to Maine to fish for Atlantic salmon, but through a combination of dams, pollution, and over-fishing we’ve done an excellent job of eradicating U.S. Atlantic salmon runs. Maine is the last North American place south of Canada where there are Atlantic salmon, but they’re critically endangered.

There are largish native wild brook trout left in Maine, when they’ve otherwise disappeared from the rest of their U.S. native range. Generally they can’t compete with rainbow trout introduced from the Pacific Northwest and brown trout from Europe, so outside of Maine they’ve been marginalized into smaller streams, and there’s not sufficient food in the streams to grow big fish. But in Maine for whatever reason they’re still the inland fish of choice.

Along with the brook trout there are also landlocked salmon. Landlocked salmon are Atlantic salmon that at the end of the last glaciation were cut off from the ocean. Apparently they make their spawning runs from lake to river in September, and they’re absolutely right to do so. September is always the best time to travel, when temperatures are starting to cool and the kids are back in school.

The last of the large native brook trout in the U.S. are a good enough excuse to see the Maine woods, but there’s also a sporting tradition. Train travel opened the Maine woods to both Henry David Thoreau and lots of traveling fishers and hunters. By the end of the 19th century, Maine fishing and hunting camps were scattered through the far Maine woods, and they were the very thing. We’re going to Libby Camp, which can trace it’s ancestry to the 1880s, but there are plenty of others. There are few things as iconic to a fly fisher as a Maine camp.

We know there can’t be a fish because the angler is wearing a red shirt. He must have dropped his hat.

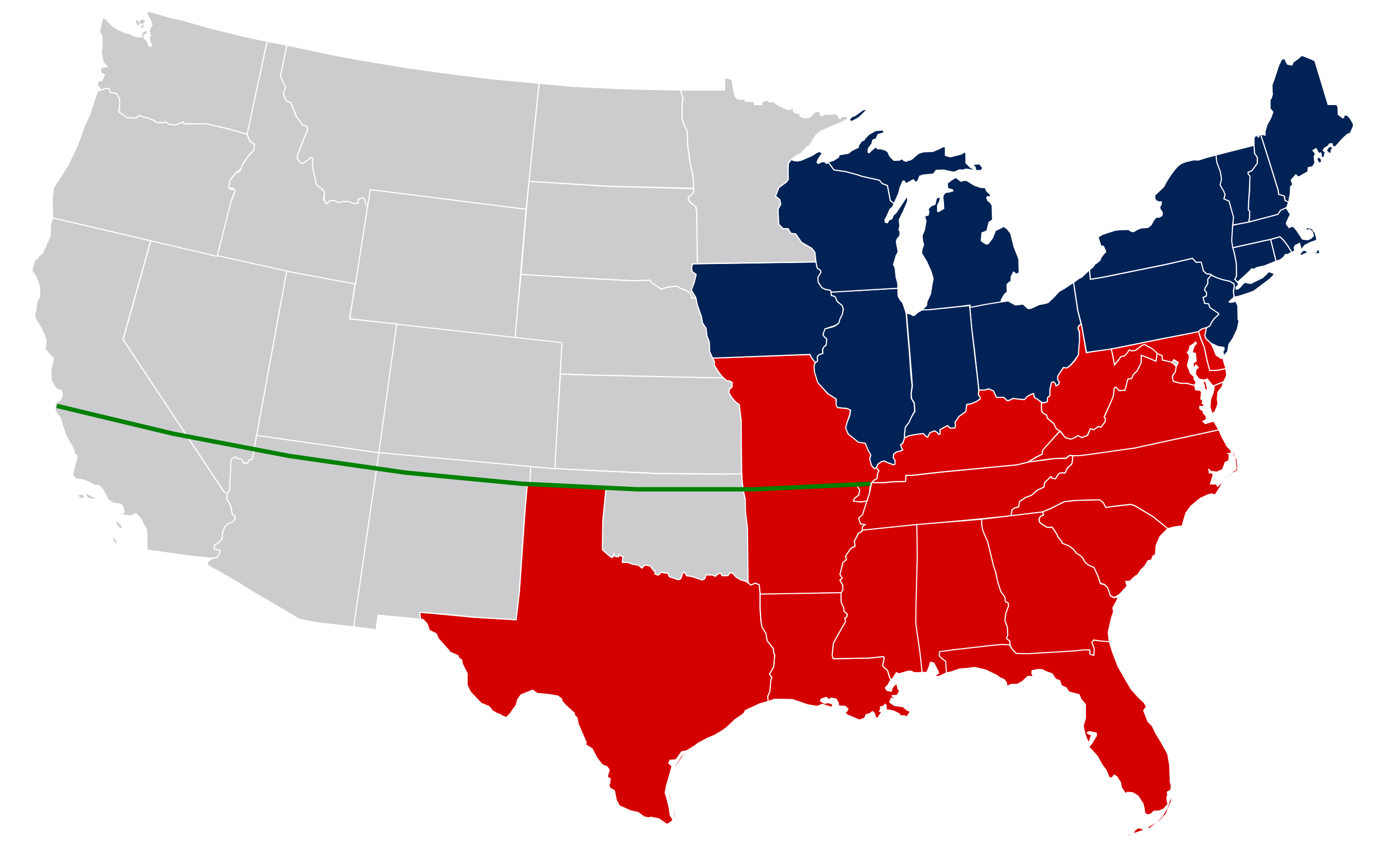

In other matters, Mainer’s didn’t vote for Donald Trump in either 2016 or 2020, voting 48.2%, or 357,735, for Clinton, and then 51%, or 435,072, for Biden. Interestingly–and this is repeated in other states as well–there is more than a 3% drop in votes for the Libertarian candidate between 2016 and 2020, from 5.09% for Gary Johnson in 2016 to 1.73% for Jo Jorgensen. One supposes two things, that about 2% of the population really does vote Libertarian, and that in Maine in 2016 about 20,000 voters wouldn’t vote for either Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump. In 2020 most of those 20,000 voters were either more enthusiastic about Biden or less enthusiastic about Trump.

There was 73% eligible voter turnout in Maine in 2016, then 78% turnout in 2020. That’s huge turnout. To put that in perspective, turnout nationally in 2020 was 66.7%.

Maine 2020 presidential election results by county, Wikipedia. That would also double for a pretty good population map.

Maine does something peculiar with its electoral college votes in presidential elections that I don’t think is done anywhere else. Instead of all or none, it splits two of its four electoral college votes by congressional district, so in 2020 Trump took one electoral vote and Biden three others. That was the only electoral vote for Trump from New England. It’s not a bad way for the electoral college to work, though unless other states did the same thing it only hurts Maine’s overall majority.

Neither of Maine’s Congressfolk are Republican, though one of its senators is a moderate Republican, which along with Atlantic salmon is a critically endangered species. Unlike the rest of Mainers, she doesn’t have a reputation for being particularly independent. The other senator, Angus King, is in fact independent, but caucuses with the Democrats.

Both Maine’s state senate and house are mildly Democratic. Its governor is Democratic.

One last note on fly fishing in Maine. Mainers created some of the most beautiful streamer flies in the American catalogue. They’re simpler variations of classic British salmon flies. I tried to tie some, though it was hard, and my results were decidedly mixed. I’m sure they’ll look a lot better in the water, and just fishing them is enough of a reason to go to Maine, whether or not I have a red shirt.