Gear

We took waders and wading boots. It was March and still cold, so we also took sweaters and rain jackets and gloves and knit caps. We took long underwear. We needed the sweaters, and long underwear helps when you wade in cold water, but the gloves (and the mukluks) were a bit of overkill.

I‘ve written already about my new/old bamboo rod. I used a 6-weight, weight-forward floating line with a 9-foot 4X leader, which is meaningful if you fly fish but gibberish if you don’t.

I used a Hardy Duchess reel, which is a newer reel that harkens back to designs from before the last World War, or maybe the one before that. It’s handmade in England, is very pretty, and most of all it looks right with a bamboo rod.

You don’t really use a reel when you fly fish for freshwater fish. To bring the fish in you just pull in the line by hand and let it pile up at your feet, so honestly the reel has a lot in common with ear rings or the color of a car’s paint job. It’s meaningful but not essential. That means that for no rational reason your reel needs to be as pretty as possible. The Hardy is very pretty.

I caught my wee trout on a dry-dropper rig, a dry fly floating on the surface so that I could see it and a trailing nymph underwater. The dry fly was a #14 Royal Wulff, which seems to be my go-to dry these days, and the nymph was a random #14 pheasant tail mayfly nymph that caught my eye when I poked through my fly box. I watched the dry fly so that when it went under, I knew the fish had taken the nymph.

Whiskey

By law, when you go to Kentucky, you are statutorily required to visit at least one whiskey distillery for each day you’re in the state. Kentucky makes it convenient by locating a distillery every 37 feet. We were in Kentucky three days and met the statutory minimum for distillery visits.

What is or is not bourbon is defined by statute. It must be corn-based, and it has to meet certain standards during distilling and aging. Whiskey taxes were a significant source of revenue for the federal government in the 19th century, and 1897 laws regulating bourbon pre-dated the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act. By 1900 if you were buying bonded bourbon, you were buying something that didn’t contain lead, or wood alcohol, or any number of other things that shouldn’t be in the bottle. Not that it was good for you, it just wasn’t as bad as it might be.

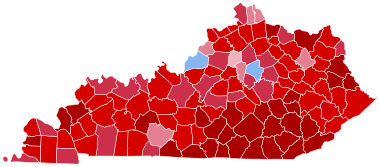

Other than being American, bourbon doesn’t come from a particular place. It doesn’t have to be made in Kentucky. There are bourbon distilleries located in places like Indiana and Ohio and Texas, but Indiana bourbon just doesn’t trip off the tongue. When one thinks of bourbon, one thinks of Kentucky.

There is a side-note here, about water. A waitress in Southern Kentucky apologized to us for Kentucky’s lousy drinking water. I’m guessing that she was saying that her local water was poor quality, but the area where bourbon historically comes from, the area of North-Central Kentucky west of the Appalachians, actually has great water. That’s one of the reasons that bourbon is made in Kentucky. Well, great water and corn. Well great water and corn and money.

When we fished the Driftless in the Midwest I learned that what makes the Driftless special is its karst topology. Karst is characterized by relatively porous sandstone, dolomite, and limestone lying close to the surface and from time to time poking through. In Kentucky, the rock is mostly limestone. Water that seeps underground fractures the rock–Kentucky’s caves, including Mammoth Cave, are the products of fractured and hollowed limestone. Water literally runs through the fractures and seeps through the pores, and the pressure from rain forces clean and mineralized water out at springs. There are springs everywhere. For fly fishers, it’s one of the best things going. The resulting spring creeks, clean and enriched, support plenty of bug life, which in climes further north support trout and should support smallmouth in Kentucky. It’s also one of the best things going for whiskey.

Over the course of a couple of days with an additional day fishing, we toured the Buffalo Trace, Makers Mark, and Woodford Reserve distilleries. At Woodford Reserve, the tour guide distilled (get it? get it?) whiskey making for us: whiskey making is making beer and then distilling the beer to clean out the mess and concentrate the alcohol. It’s not, he told us, very good beer, but I guess bad beer makes pretty good whiskey. To be bourbon, it has to be at least 50% corn-based and and the distilled beer must be barrel-aged in new oak barrels. There’s no minimum time for aging, but the longer it ages, the better it should be, but the longer it ages the more loss there is from evaporation, the longer it has to be stored, and the more expensive it all becomes.

There are few things that smell better than a warehouse full of aging bourbon in oak barrels.

Where We Stayed

We stayed in the 21C Hotel in Louisville. It’s the third time we’ve stayed in a 21C. The other times were in Bentonville, Arkansas, and in Kansas City. They’re a bit pricey, but they are unbelievably friendly to pets, have interesting art everywhere, and lurking red plastic 4-foot penguins that you can move around in the hallways to disturb your neighbors. The first of the 21C Hotels were in Lexington and Louisville.

Louisville is not a rich city. Kentucky is a poor state generally, and I guess it always has been. After all, Daddy sold a hog each fall to buy us kids shoes. On the flip side, there’s a lot of wealth–just drive down a horse-farm back road. Those splits, poverty/wealth, whiskey/conservative Protestants, urban/country, they all seem harder in Kentucky than in other places, at least harder than I’m used to. Kris thinks I’m making it up. She thought Louisville was great.

Where We Didn’t Go

I never made it to the Louisville Slugger Museum. It was two blocks from our hotel, and I never made it.

We never made it down by the Green River where Paradise lay. We never saw Appalachia from the Kentucky side (we’ve been to West Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania), or Mammoth Cave.

Restaurants

I wouldn’t write home about the donuts or the barbecue, but Louisville has pretty good restaurants. We ate at the hotel one night, at Proof on Main, and the next night at a very good interior Mexican food restaurant, Maya Cafe. The last night we ate at at Everyday Kitchen, and to my eye its menu had a lot of East European food. East European food is to me mighty exotic, it’s just not something I’ve seen very much of, and at the same time it’s completely comprehensible, like Mom’s home cooking. My brushes with East European food in Milwaukee and Chicago and Louisville may be one of the things I like most about the Old Northwest.

I had stuffed cabbage.

The most remarkable thing about the restaurants in Louisville was the amount of whiskey on the menus. There were moderately priced whiskeys by the barrel, and expensive whiskeys that made fly reels look cheap. There were pages of whiskeys, regiments of whiskeys, whiskeys waiting in the wings just to get on stage. I didn’t know there were that many whiskeys in the world.

Mind, that picture only starts with the letter “O”. There were 13 letters of the alphabet preceding. Those aren’t bottle prices either.

Route

Going out we drove from Houston to Nashville; coming home we left early and drove straight through. There are more eighteen-wheelers on the road from Little Rock to Memphis than there are distilleries in Kentucky. If I ever drive to Kentucky again, I’ll drive through Louisiana.

Music

What a lot of music there is from Kentucky. There’s not a lot of jazz; Les McCann and, if you stretch it as to the jazz, Rosemary Clooney. There is a lot of bluegrass and country. Besides Loretta Lynn, there’s the Monroe Brothers, Tom T. Hall, Crystal Gayle, The Judds, Rickey Skaggs, Merle Travis, and Dwight Yoakum. “Don’t It Make My Brown Eyes Blue” isn’t nearly as bad as I remember it.

I looked forward to Sturgill Simpson and My Morning Jacket coming up on the playlist. Simpson put out Metamodern Sounds in Country Music in 2014, and a A Sailor’s Guide to Earth in 2016, and both albums astonish me, as much for the lyrics as the music. “Turtles all the Way Down” is a country song about Jesus, or Buddha, or LSD, or the turtle that holds up the world. Or something.

My Morning Jacket always satisfies.

And then there are the 37 versions of John Prine’s “Paradise.” John Fogarty, Johnny Cash, John Prine, Tom T. Hall, Dwight Yoakum, Jackie DeShannon, John Denver, Roy Acuff, Tim O’Brien . . . And Sturgill Simpson. Everybody’s recorded “Paradise.” I think if you are from Kentucky, you have to record a cover of “Paradise” before you’re allowed to open a distillery.

Guitar

I took the Kohno, and played a good bit. I’ve been working on the first movement of Bach’s 4th Lute Suite, but I can never get much past page 2, and it’s a lot longer than two pages. I’ve also been working on songs I once knew but don’t know any more–an arrangement of Summertime, some Tarrega, some Sanz, and a transcription of Albeniz’s Cadiz. That’s gone a lot better.